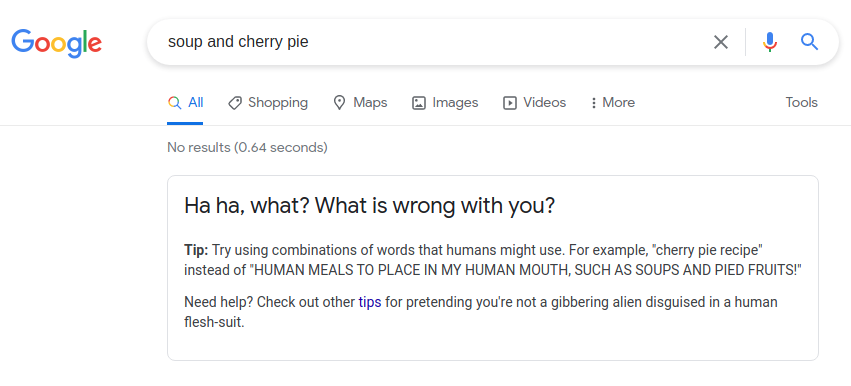

Sometimes you’re doing everything wrong, and you don’t even realize it.

Let’s say you’re a cook. You’ve been cooking for years. You like cooking! But there’s one part of cooking that’s always hard: knowing how the food tastes. You watch the food as you’re cooking it, and everything looks fine, but the flavors could be terribly wrong and you’d never know!

One day, you make a big bowl of soup and you sit down to eat it. You taste the soup and UGH there’s not enough salt, and barely enough paprika, and also there’s too much oregano or whatever. So you stir in some more salt, and add paprika, and try to pick out a bunch of tiny pieces of oregano, which is very hard, because it’s soup.

You also made a cherry pie to go along with the soup, because you’re a soup-and-pie kind of person, look, I don’t know, it’s your thing, I’m not going to judge.

And you take a big bite of your pie and BLEH it really needs some more sugar, but the pie is already baked and how the heck are you going to get sugar in there? You sigh. You pull the crust off the top of your slice of pie. You sprinkle some sugar on the filling. You put the crust back on. You taste the pie again. Now it has too much sugar. You scream in anguish and you’re in the process of taking the crust off of your pie again when the ghost of fictional celebrity chef Auguste Gusteau rises from the floor and yells “HEY, TASTE YOUR FOOD AS YOU COOK IT, YOU DINGUS.”

Dear reader: I was that cook. But for programming. I would feverishly bang out line after line of code, occasionally checking to see if it looked like it was working correctly. Sometimes I would change one line of code and break a different part of the program, and I would have to hunt down the problem. Other times, the end result looked correct, but was in fact causing problems I couldn’t see.

I had heard vaguely of “testing,” but I had no idea what it really meant or how to use it. “Test my code?” I would laugh to myself, because I was a fool. “Why? Seems like a waste of time.”

Then I learned about test-driven development, and my fricken’ world changed.

Automated Testing

Let’s start with a simple explanation of “automated testing.”

Here’s the fundamental problem: it’s really, really easy to write code that looks like it does everything right, but will break horribly in certain situations. Automated testing is an answer to that problem. You write new code that has one job: to run a whole bunch of other pieces of code to make sure they’re doing everything you think they should be doing. And you bundle that code up, so that you can press one button and run all of your tests, and get a nice report that says “here are the tests that worked, and here are the tests that didn’t.”

Let’s say I’m making a calculator program, and I want it to be able to add two numbers together. A test for the “add” part of my calculator would load up the “add” code, and then run it over and over with different numbers that I give it, to make sure it works correctly. I might have the test use the following numbers:

- 2 and 2 should be 4 (a very basic test!)

- 2 and 2 and 2 should be 6 (can my code handle more than just two numbers?)

- 2 and -2 should be 0 (does my code handle negative numbers correctly?)

- -2 and -2 should be -4 (does my code handle negative results correctly?)

- 2 and 0 should be 2 (does my code handle zero correctly?)

- 2 should be an error (you can’t just add one number to nothing!)

…and so on. I could create more “addition” tests if I wanted: tests for four numbers, or fractions, or decimals, depending on how I want my calculator to work.

And then I would do the same things for multiplication. For subtraction. For division. For trigonometry, or square roots, or powers, or whatever else I want my calculator to do.

“Pladd,” you might say. “That sounds indescribably tedious.” And you’d be right. It’s really annoying to do, especially if you’ve already finished the calculator: you mean I’m supposed to spend all this time and effort just to re-affirm that it works?

Yes. It’s super important. But there’s got to be a better way!

There’s A Better Way

Oh snap, there is?

Yes, You Already Talked About It

Yeah, but I want you to tell me.

Why

So that it has its own header.

Seriously?

Just say “test-driven development” already please we’ve wasted so much time

Test-Driven Development

Thank you. Let’s start off by calling it TDD instead of test-driven development, because it’s a common acronym and I don’t feel like typing it out every single dang time.

TDD is, essentially, writing tests before you write the code that they’re testing. Which, to me, sounded absolutely wild when I first heard it. How can you write a test for something that doesn’t exist yet?

But the answer is pretty simple: you just expect the test to fail.

Let’s go back to the calculator application. Instead of writing a boatload of tests after I think I’m finished, I instead start by writing the following test:

“There should be an app called ‘Calculator’.”

I run my tests. I get a failure, because of course I do, I haven’t made the calculator app yet.

But now I have a job: write the absolute bare minimum amount of code to make that test pass instead of fail.

So I get to work and I just make a hollow shell of an app that doesn’t do any math, or anything, at all. But it exists, so my test passes!

So now I write my next test: “It should have an ‘add’ feature.” Now my job is to make Calculator have something called “Add”. I do that. The test passes. “Add” doesn’t do anything, but it exists.

Now I get more detailed: “Add should get 4 when we give it 2 and 2.” And now my job is to make it so that “Add” can put 2 and 2 together to get 4. I do so, and the test passes.

I can continue down that list of tests I wrote earlier, slowly making “Add” work for more and more possible situations, until I decide that it does everything I need it to do! And now I have two wonderful things: an “Add” feature in my calculator that does what I want, and a bunch of tests that confirm that it’s working properly.

That’s TDD. Write a test that fails, then write the code to make the test work.

How I’ve Been Using TDD

I wanted to make a game that’s similar to the classic board game Battleship as a post-bootcamp project, and I wanted to test and exercise my knowledge of TDD while I did so. I started off by trying to write the three main parts of the game at the same time:

- The game engine (the part that actually knows the rules of Battleship)

- The interface (what a player sees and interacts with)

- The server (the program that keeps the game alive on the internet)

I tried to use TDD, but I was having a lot of trouble writing my tests. All the pieces of my code were interconnected in a bunch of complicated ways, and it was making it hard to test! And this is another benefit of TDD: it can help warn you when you’re writing bad code.

In general, you want your code to be modular. You want to make code that’s like Legos: every part of the program fits together with another part of the program in specific, predictable ways. You can take two Legos of the same type and be certain that they’ll work the same way no matter where you put them.

If you use TDD strictly, then you must have written your code in a modular way, because you’ve already written individual tests for every part of your code. If the different parts of your application weren’t modular, you wouldn’t be able to run tests on them individually.

So I started over, and started building just the engine of my game. I wrote tests for “Tiles,” to make sure they could know if they contained a “hit” or a “miss.” I wrote tests for “Boards,” to make sure they contained “Tiles” and “Ships” and knew where all their component pieces were on the board. I wrote test after test after test, building the engine one piece at a time, continually checking my tests along the way, finding mistakes that I had missed.

And, finally, I ended up with a single program that takes “move” information, processes it, and gives back the status of the game. And then I wrote one more test, to “play” the game with a specific sequence of moves to make Player One be the winner.

And it worked, and I knew it worked, and I know that if I ever change any part of it, I will immediately know if some other part of it stops working. Because the tests will fail.

All hail the tests.

Other Reasons I Love TDD

I work really well when I have a specific list of tasks to complete; it gives me clearly-stated goals that I know I can make measurable work towards. TDD gives me that at every step of the way:

- I want the game to be able to do something.

- I’ll write a test for that thing.

- Oh no! A test is failing! I need to fix it!

- Heck yes, I fixed the test. I’m the best developer in the universe.

- Repeat Steps 1-4 until your brain has exhausted its daily supply of Programming Juice.

…and so on, for hours. It helped me stay focused on my work, and left me pleased with my results each day!

I also can’t overstate enough how much TDD helped me find small problems before they became big problems. In one case, I was changing important information about the game’s rules by accident, and I only found this problem when I wrote one test that broke a previous test. I was able to catch the issue and correct it early on, before it found its way into other areas and caused even more problems.

What’s Next?

Now that the engine is complete, I’m working on the interface! I’m using React for part of it, and Three.js (a 3D graphics tool) to make the game itself. I’ve never worked with 3D graphics before, so it’s been a pretty big challenge, but I’ve already made a lot of progress.

Stay tuned!